To get an idea of how complex the shown interactions are in the process of overcoming the force of gravity, straightening, orienting the body and moving towards the goal, it is best to know all this in practice; practical experience is remembered best.

Below it is proposed to make a small experiment on yourself with an analysis of the results.

To do this, lie on your back, slowly turn on your side, slowly get up and start moving forward, for example, to open a window.

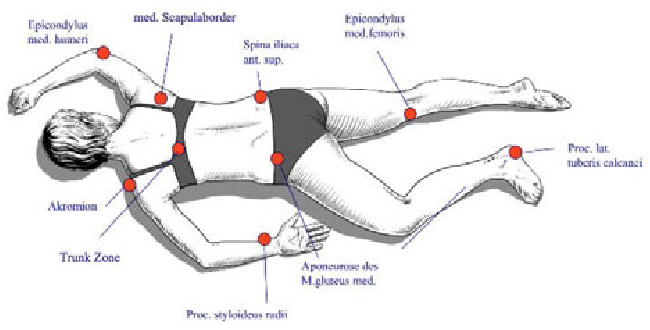

If you perform individual steps slowly, almost at the pace of slow motion filming, you can observe how the supporting surfaces change. Support surfaces are the places where the body rests on the floor in order to rise up. You can try to get up from either side. Perhaps then you will find a preferred side from which it is easier to get up. An accurate observer will notice that during the whole process, the supporting surfaces become smaller, the balance is more and more unstable, and more and more work is required to overcome the force of gravity and lift the body.

In the supine position, you are still lying on a fairly large supporting surface, but when you turn to the side, the support decreases. At the end of the turn, the upper body rests only on the shoulder joint and forearm, the lower part only on the pelvis and hip joint. In order not to complicate the whole process too much and not to limit the spontaneous course of movement too much, we deliberately do not consider here the movements of the hands and the stepping movements of the legs when walking.

Next, you need to lean on the forearm of the lower hand in order to rise and move the body weight to the pelvis.

The weight of the lower side of the body is distributed on the thighs, the outer surface of the thigh and lower leg, the outer edge of the foot. Then the hand from above takes over the task of support, then the hand from below. Then the weight of the body rests on the knee from above. This allows the lower leg to bend. You can first lean on your knee, or, with sufficient dexterity, immediately set the foot. Then the second foot is set, the hands come off the floor, the body straightens and stands on the feet. Now you can go ahead to achieve the goal of the movement set at the very beginning of the process, that is, open the window.

We have considered, in a rather rough approximation, the path from the position on the back through standing up to the process of walking. But is this enough to give a small practical example of what it means to overcome the force of gravity, and how you can rise up by transferring body weight and changing the supporting surface?

If you repeat this upward path more often, you will notice that both sides of the body have taken on various supporting, carrying and moving functions in the phases of lifting and straightening the body. This is due to the fact that both sides of the body complement each other in purposeful movement from the position of “lying on the back” to walking on two legs. As a result of constant weight transfer, there is a change of supporting and mobile elements. Associated with this change is the constant regulation of equilibrium.

In addition, one can observe how the torso, and hence the spinal column, was noticeably involved in performing the functions of holding and turning. The arms and legs were used as levers in the straightening process. In the course of such a seemingly simple action, one could already feel all three inextricable relationships named above:

- body posture alignment

- straightening against gravity

- and moving towards the target.

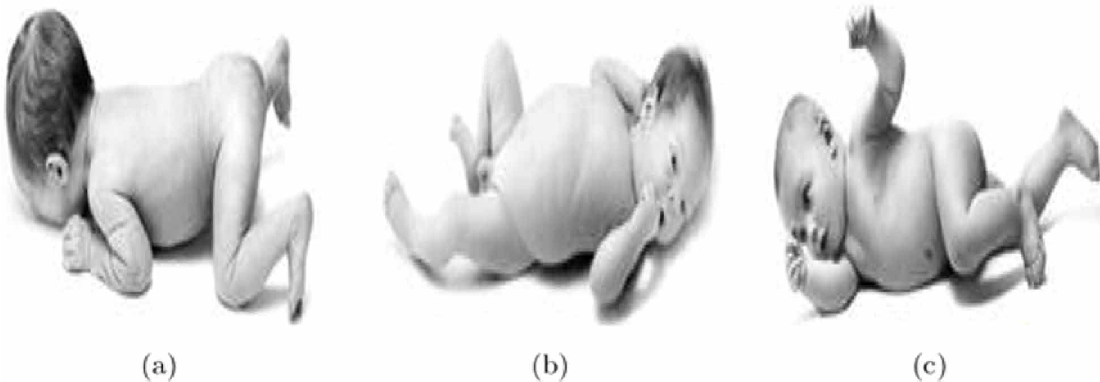

In addition, motor algorithms were used to maintain the posture and move the torso. As a rule, such algorithms become available for a child at the age of about 3 months in the supine position with a flip on its side, and the child can stand up at the age of 9-10 months

It may be objected that there is nothing special in performing the above movements. Indeed, a person with normal processes of maintaining a posture and performing movements does not think at all about what prerequisites must be implemented in order to be able to perform supposedly simple movements. But for people suffering from a movement disorder, for whom the appropriate motor algorithms are not available, these processes can turn into an insurmountable obstacle.

Usually any healthy person continuously changes body postures.

With each change in posture, the CNS is abundantly supplied with new stimuli from the skin, muscles, tendons, and internal organs, and the CNS continuously sends commands to correct each posture. The processing of these stimuli and the response to them occurs in the sensorimotor system by adapting existing motor algorithms with changes in posture.

Thus, in the supine, side-lying, side-sitting, hands-on sitting, and feet-standing positions as shown in the example above, all of these positions require constant adjustment. Every straightening and every movement requires a posture, even in a child with his spontaneous movements and spontaneous motor skills. To assess spontaneous motor skills, this posture is very carefully analyzed and described. The movement that the child shows is considering